Erected nearly 3,800 years ago, Hammurabi’s Code is a monumental record of Babylonian law, etched in stone to define standards of justice, punishment, and royal legitimacy. With 282 specific laws covering contracts, medicine, trade, and family law, the code wielded the principle of “an eye for an eye” to balance social hierarchy with legal clarity. As one of the world’s earliest civil law compendia, it reveals much about ancient power, social order, and the origins of written authority.

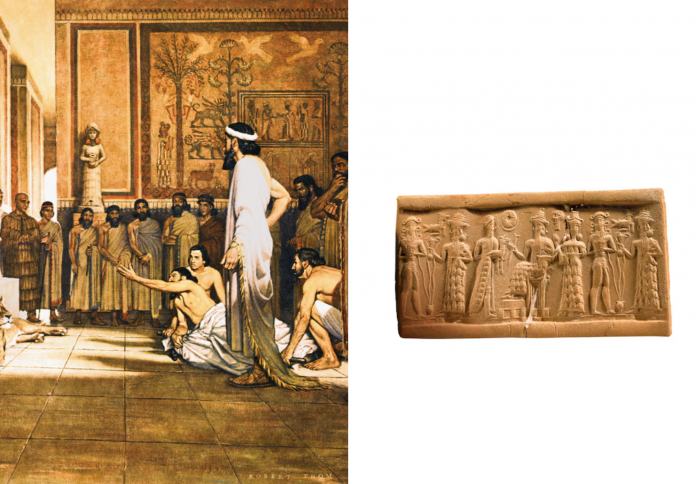

Law as divine mandate and sovereign display

Hammurabi, the sixth king of Babylon, declared that he received his laws from Shamash, the god of justice. By inscribing the code in diorite stone and placing it in public view, he transformed legal enforcement into symbolic statecraft—firm, visible, immutable. The king’s image, framed under Shamash’s rays at the stone’s head, signaled that obedience was both civic and sacred. The public nature of the stele emphasized transparency, permanence, and unity under one legal ruler.

By consolidating earlier subtler practices into a unified legal structure, Hammurabi’s Code signaled the emergence of a cohesive empire. The laws were accessible, structured, and intended to govern daily life across social classes—from wealthy merchants to laborers and slaves—under a single legal ethos.

Structured laws with unequal consequences

Although the code follows consistent “if–then” logic, punishments varied significantly by social status. Babylonian society was stratified into nobles, free citizens, and slaves; an offense’s penalty depended on the victim’s position. For instance, causing bodily harm to a noble might warrant equal harm in return, whereas harming a slave often resulted in monetary reparations. This structured inequality affirmed hierarchy while allowing a controlled form of reciprocity—codifying justice with strict class awareness.

The lex talionis approach ensured predictability in penalty, but reinforced social order. Part of the Code’s function was to protect higher-status individuals, keeping acts of violence calibrated to preserve the status quo rather than promote true equality.

Emerging procedural safeguards in legal culture

Despite the Code’s severity, certain laws point toward early judicial fairness. The accused could present evidence or witnesses, challenging arbitrary conviction. At least one law required proof before accusing another of serious wrongdoing, hinting at procedural awareness centuries ahead of similar Western legal doctrines.

Though justice often favored the powerful, the presence of such articles suggests nascent legal reasoning beyond punitive instinct. Judges were instructed to follow findings rather than hearsay, and order in society was maintained through documented precedence, not only the whim of rulers.

An enduring legacy of legal visibility

Centuries later, Hammurabi’s Code became a reference for civil legal systems far beyond Mesopotamia. Its clear structure and public declaration influenced laws in the Hittite, Assyrian, and even Biblical traditions. Many historians regard it as a precursor to modern legal systems, where laws are written, published, and applied to specified cases.

Although buried and forgotten for millennia, the Code remains culturally resonant—its stele reconstructed in museums worldwide, and its influence subtly echoed in modern legal symbolism. It reminds us that written law became the most powerful tool for shaping societies—and that even ancient rulers understood the importance of aligning legal order with divine and political legitimacy.

Through its structure, clarity, and intentional unevenness, Hammurabi’s Code casts a long shadow over legal history. It articulates an early version of civil organization, hierarchy, and the paradox of justice in a stratified world—foreshadowing many challenges and ideals modern societies still navigate today.