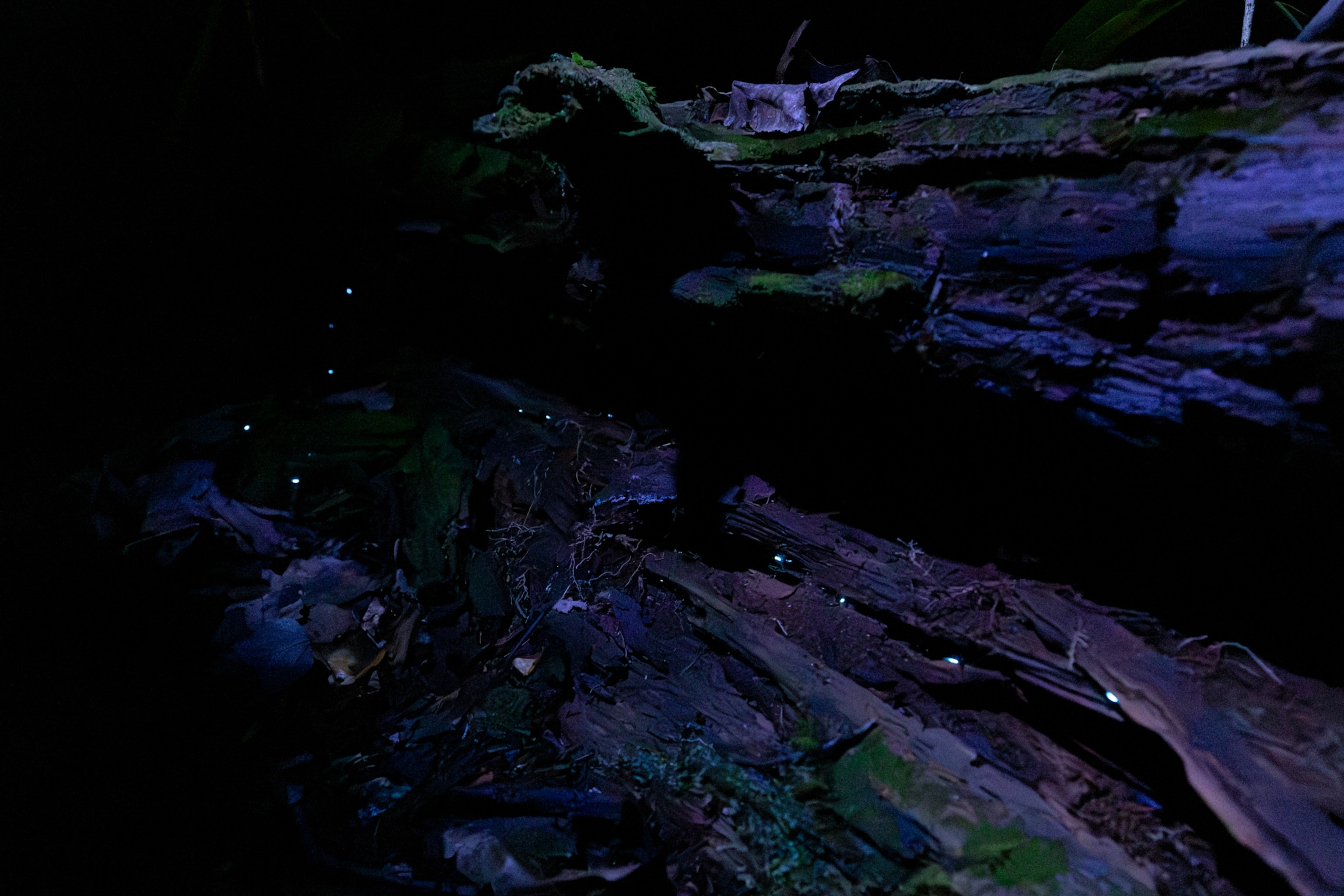

In the lush darkness of the Appalachian Mountains, tiny larvae known as Orfelia fultoni alight upon mossy embankments and canyon walls with an electric blue glow. Unlike familiar fireflies, these forest-floor dwellers shine from both ends, weaving sticky webs to lure prey—and enchant visitors. This understated phenomenon, often seen in spring and autumn at places like Grandfather Mountain, Pickett State Park, and Dismals Canyon, redefines our expectations of nocturnal life in North America.

A blue‑light spectacle hidden in plain sight

These creatures, sometimes called “dismalites,” are actually the bioluminescent larvae of a fungus gnat species endemic to the Appalachian region. Measuring barely over a centimeter, they emit one of the bluest lights ever recorded in any insect. Their range extends from North Carolina to Alabama, but they’re seldom noticed—until observers switch off headlamps after dark and let their eyes decelerate into night vision.

Instead of wasting time in flashy aerial displays, the glowworms cling to damp cavern walls or logs, their pinpricks of blue light illuminating mossy crevices like tiny constellations. In some hotspots—on cool, humid nights in May and September—dense populations turn creekside banks into silent fields of stars, visible only when ambient light is stripped away.

Bioluminescence designed to seduce and ensnare

This steady blue glow isn’t merely poetic—it’s functional. Emerging at both ends of their bodies, Orfelia fultoni larvae attract tiny flying insects toward mucus strands woven between surfaces. The structures resemble spider silk but are secreted glue that snares prey in flight. Once trapped, the larva subdues its catch—an efficient and eerie strategy for a creature scarcely bigger than a thumbnail.

Scientifically, their light is created through luciferin-luciferase chemistry, consuming oxygen to yield the visible glow. Intriguingly, despite being relatives of glowworm species in New Zealand’s caves, Orfelia fultoni produces its blue radiance through a distinct biochemical process—a compelling example of convergent evolution in nature’s light show.

Dark trails and guided hikes: honoring a fragile habitat

Because these glowworms are light-sensitive, finding them requires more than dark clothes—it demands darkness itself. When visitors use white lights at night, the larvae halt their glow or retreat into crevices. That’s why guided night hikes at places like Pickett State Park (Tennessee) and Dismals Canyon (Alabama) enforce headlamp-free or red-light protocols until reaching glowworm zones. Only then are lamps shut off and night vision allowed to unfold—revealing a faint galaxy beneath your feet.

As humidity, canopy shade, and undisturbed stream banks define their survival, even mild environmental change—light pollution, trail trampling, invasive history—can diminish these gatherings. Visitors feel awed, but entomologists and park staff urge vigilance: even minimal exposure can clutter the larvae’s behavior or habitat permanence.

Why Appalachian glowworms matter more than their glow

Beyond being unexpected spectacles, these glowworms remind us of what quiet nature can hold beneath our nightly feet. They’re the only known bioluminescent fly species in North America, and their subtle light challenges what we expect from ‘macro’ nature. Standing among them—eyes adjusted, breath silent—you feel entangled in an ecological system that transcends visibility, one where darkness and light share delicate balance.

While fireflies and mushroom glows are more visible, the blue hum of Appalachian glowworms is a still, soulful signal of a forest’s health—and fragility. They exist at the intersection of biology, chemistry, and habitat preservation. And perhaps most importantly, they reconnect night walkers to wonder at a scale finely tuned to humility.