In the heart of Gothenburg, Sweden, a powerful debate is raging, one that pits the forces of progress against the value of preservation. The city’s historic Valhallabadet swimming pool, a cherished modernist icon and a vital community hub, is slated for demolition to make way for new sports facilities. Yet, this decision has ignited a passionate and vocal protest from a coalition of architects, writers, and conservation groups who argue that tearing down the 1956 building would be a grave mistake. They contend that the pool, with its rich history and significant architectural design, is a testament to the city’s identity and that its demolition would be a “waste of history.” This struggle for Valhallabadet is not just a local skirmish; it is a microcosm of a broader, global conversation about the fate of modernist architecture and the urgent need to balance urban development with the preservation of cultural heritage and embodied carbon.

A Modernist Icon Under Threat

Designed by architect Nils Olsson and opened in 1956, Valhallabadet is far more than just a swimming pool; it is a significant piece of architectural and cultural history. The building’s design, characterized by clean lines, functional spaces, and a bold, modernist aesthetic, was so groundbreaking that it was awarded an Olympic bronze medal in 1948, well before its completion. It is a prime example of Swedish functionalism and has served as a meeting place and a center for sports and recreation for nearly seven decades. The pool’s interior also features a large, breathtaking mosaic by renowned artist Nils Wedel, an invaluable piece of public art that is integral to the building’s identity.

For generations of Gothenburg residents, Valhallabadet is a place of deep personal significance, a space where countless people learned to swim, trained for competitions, or simply spent a day of recreation. Its demolition would be the loss of a vital community hub and a living piece of history. The protestors, including the conservation group Föreningen Fasad, believe that the building’s unique character and architectural merit are irreplaceable. The fact that Europa Nostra, a leading European heritage organization, has named Valhallabadet one of Europe’s most endangered sites underscores the international significance of the protest.

The Case for Preservation

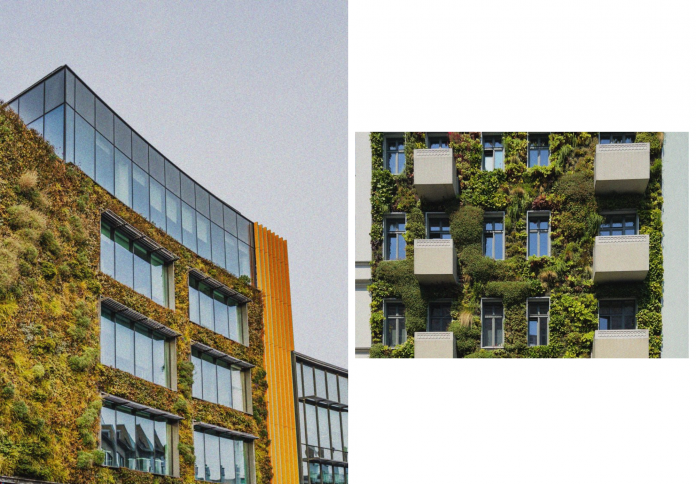

The arguments for preserving Valhallabadet are multifaceted, extending far beyond sentimental nostalgia. At its core, the protest is a powerful statement on the principles of sustainable design. Tearing down a building of this size and age would result in a massive loss of “embodied carbon”—the energy that was used to construct it in the first place. Architects and environmentalists argue that from a climate perspective, it is almost always more responsible to renovate an existing structure than to demolish it and build a new one. The energy and resources required to construct a new swimming hall would be enormous, creating a significant environmental footprint that could be avoided by a more thoughtful approach.

Beyond the environmental case, protestors emphasize the building’s cultural and social value. They argue that Valhallabadet has become a vital part of the city’s social fabric, a place that brings people together from all walks of life. Its demolition would not only erase a piece of architectural history but would also destroy a vital community meeting place. Protestors believe that there are alternative solutions, such as finding a new location for the planned sports facilities or re-purposing the existing building for a new function, that would allow the city to meet its future needs without sacrificing its past.

The City’s Counter-Argument

The city of Gothenburg, however, maintains that the demolition of Valhallabadet is a necessary step. The city’s vice chairman, Daniel Bernmar, argues that the pool, despite its history, is outdated and no longer meets the needs of a modern city. He claims that the building is in need of extensive and expensive renovations, and that even with these improvements, it would not be large enough to serve the current demand of over half a million swimmers annually. From the city’s perspective, a renovation is not economically justifiable, and building a new, larger, and more efficient facility is the only long-term solution.

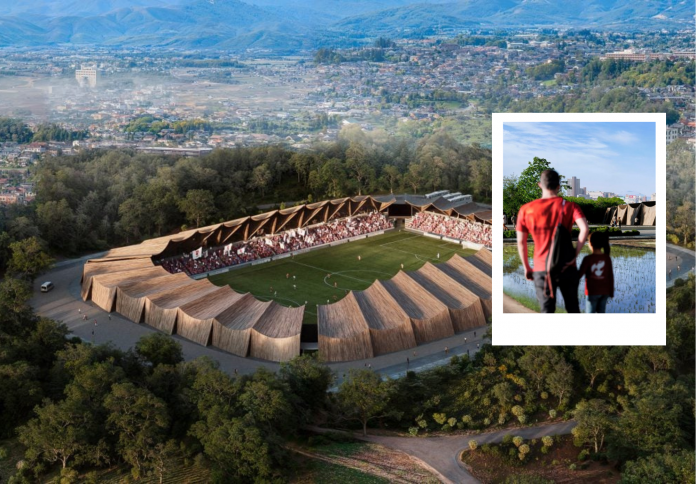

The city also suggests that the new, centrally-located sports facilities will be an architectural landmark in their own right, a building that can proudly represent Gothenburg in the 21st century. The argument is one of pragmatism versus idealism. The city believes it is making a financially responsible and forward-thinking decision, while protestors believe it is a short-sighted and culturally damaging one. The city’s position highlights the difficult choices urban planners face when trying to balance the needs of a growing population with the desire to preserve the past.

Lessons from a Global Debate

The struggle for Valhallabadet is part of a larger, global conversation about the fate of modernist architecture. Many buildings from the mid-20th century are now reaching an age where they require significant renovation, and their minimalist aesthetic can be seen by some as cold or outdated. As a result, many of these structures are under threat of demolition. The protests in Gothenburg echo similar movements around the world, from the campaign to save the historic Brutalist buildings in London to the debate over aging landmarks in American cities.

The Valhallabadet protest, however, stands out for its emphasis on the environmental cost of demolition. By bringing the concept of “embodied carbon” to the forefront, the protestors are framing the debate not just as a matter of taste or history, but as an urgent climate issue. This shift in perspective adds a powerful new layer to the argument for preservation and shows that the conversation around heritage is evolving to include a deeper consideration of environmental responsibility.

What’s Next for Gothenburg?

As the protest continues, the future of Valhallabadet remains uncertain. The city seems committed to its plans for demolition, but the vocal and passionate opposition may force a re-evaluation or at least a public discussion on alternative solutions. The outcome of this battle will be a significant moment for Gothenburg, a city that prides itself on its progressive and sustainable identity.

Ultimately, the fight for Valhallabadet is about more than a swimming pool; it is a question of what we choose to value as a society. Will we prioritize the efficiency of new construction, or will we find a way to honor the history, the community, and the embodied energy of the buildings that have served us well for generations? The answer to that question will define the architectural and cultural landscape of Gothenburg for years to come.