Everglades National Park in Florida preserves the largest subtropical wilderness in the United States, a slow-moving, shallow sheet of water that flows from Lake Okeechobee south toward Florida Bay, famously known as the “River of Grass.” This UNESCO World Heritage Site is a crucial haven for a rich diversity of life, boasting the largest mangrove ecosystem in the Western Hemisphere and serving as the only place on Earth where American Alligators and American Crocodiles coexist. Defined not by geological formations but by water, the Everglades offers a truly unique exploration of a dynamic, interconnected ecosystem where the boundaries between freshwater, saltwater, and land are constantly blurring.

Defining the River of Grass Ecosystem

The core of the Everglades’ unique identity is its slow, continuous flow of fresh water across a vast, flat limestone shelf.

Unlike a typical river confined to a narrow channel, the Everglades is a broad, shallow sheet of water, sometimes 60 miles wide, moving barely a hundred feet per day. This flow sustains the dominant plant life: dense beds of Sawgrass, which grow several feet high and give the appearance of an endless prairie. Scattered throughout this “river” are tree islands, or hammocks, which are slightly higher elevations where hardwood trees thrive. This entire system relies on a delicate balance of fresh and salt water, leading to a complex mosaic of ecosystems that includes pine flatwoods, cypress swamps, and the essential mangrove forests along the coast.

A Sanctuary for Unique and Threatened Wildlife

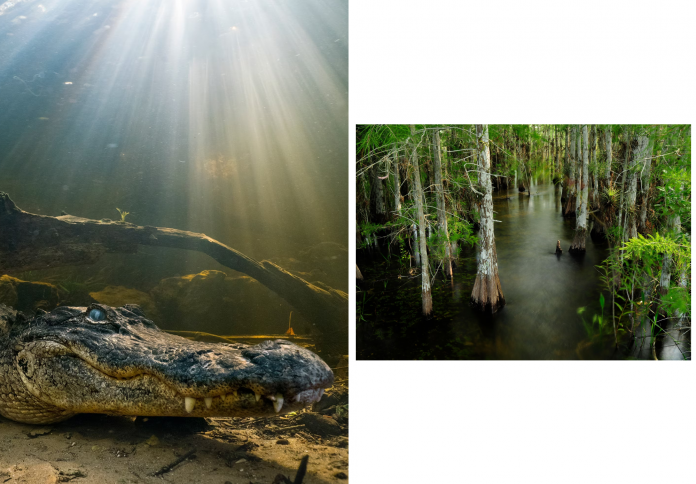

The Everglades is one of the most important wildlife sanctuaries in North America, protecting numerous endemic and threatened species that rely on its specific mix of habitats.

The park is the only place in the world where both the powerful American Alligator (prefers freshwater) and the shy American Crocodile (prefers brackish and saltwater) live together. Visitors often spot alligators basking on the banks of canals or in the Gator Holes—depressions of open water that are vital during the dry season. The park also provides critical habitat for the endangered Florida Panther, the elusive West Indian Manatee, and a staggering variety of wading birds, including the colorful Roseate Spoonbill, Great Egrets, and Great Blue Herons, which gather in large numbers to feed in the shallow waters.

Exploring the Vastness: Water and Trails

Given the park’s watery nature, the best methods of exploration are either by water or on the few constructed pathways and trails.

The main areas of visitation include the Shark Valley section, which features a 15-mile paved loop ideal for bicycling or riding the park tram, offering excellent opportunities for wildlife viewing, particularly alligators. For a quieter, more intimate experience, kayaking and canoeing through the mangrove tunnels and deep into the backcountry are highly recommended. Additionally, the park provides facilities for boating and fishing in Florida Bay and maintains several short boardwalk trails near the Gulf Coast Visitor Center and Royal Palm area, allowing visitors to walk above the swamp floor and observe the dense habitat up close.

A Story of Conservation and Restoration

The establishment of Everglades National Park in 1947 was a monumental act of conservation, recognizing the immense ecological value of an area often misunderstood as a “swamp.”

However, the ecosystem remains severely threatened by past and current human activities, particularly the massive alterations to the region’s natural water flow. Decades of drainage, damming, and canal construction upstream have diverted essential freshwater away from the park. The ongoing Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan (CERP) is the world’s largest ecological restoration effort, aiming to undo decades of damage by restoring the natural sheet flow of water. This ambitious project is critical to ensuring the survival of the park’s unique plant life, wildlife, and the delicate balance of its freshwater and marine habitats.