Denali National Park and Preserve in Alaska is a vast, six-million-acre wilderness defined by its rugged subarctic terrain, long, cold winters, and the awe-inspiring presence of Denali—the highest peak in North America. Formerly known as Mount McKinley, Denali stands at 20,310 feet, dominating the landscape and serving as the park’s undisputed centerpiece. The park’s primary goal is to preserve its spectacular wilderness qualities, which means access is highly restricted to minimize human impact. Consequently, Denali offers a premier experience in true, raw Alaskan wilderness, celebrated for its spectacular glacial geology and the opportunity to view the “Big Five” of Alaskan wildlife in their natural habitat.

The Mountain’s Presence: Denali and Its Geology

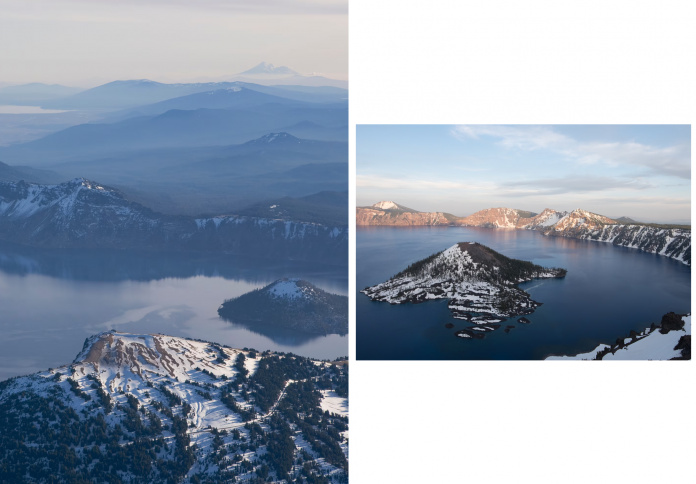

The geology of the park is dominated by the colossal Denali massif and the surrounding Alaska Range, which together form one of the world’s most dramatic mountain landscapes.

Denali is an immense, granite mountain that continues to rise due to its location near the confluence of major fault lines. Unlike most peaks, its vertical rise from base to summit (around 18,000 feet) is one of the greatest in the world, lending it a massive scale. The park’s landscape has been profoundly shaped by glacial activity, which continues today. Valley glaciers, like the Toklat and Kantishna, have carved U-shaped valleys, deposited glacial till, and created the silt-laden rivers that characterize the park’s river system. The sheer size and elevation difference create multiple climate zones, ranging from spruce forests at the lowest elevations to tundra and permanent ice fields higher up.

A Sanctuary for Alaskan Wildlife: The Big Five

Denali is world-renowned for its opportunities to view large, free-roaming Alaskan mammals in a roadless, protected environment.

The park is home to Alaska’s “Big Five”: Grizzly Bears, Moose, Caribou, Dall Sheep, and Gray Wolves. The Denali Park Road is the prime viewing corridor. The vast, open terrain of the tundra and taiga makes spotting these animals easier than in forested areas. Large herds of Caribou are often seen migrating across the open plains, while Dall Sheep dot the steep, gray-rock mountainsides. The abundance of these herbivores sustains a healthy population of predators, including the often-elusive Gray Wolves. Observing these creatures in their natural, undisturbed rhythm is the highlight of a Denali visit.

Access and Preservation: The Restricted Park Road

To preserve the wilderness character and protect the wildlife, Denali National Park heavily restricts private vehicle access deep into the park’s interior.

The 92-mile Denali Park Road penetrates the park’s heart, but beyond the first 15 miles, it is almost exclusively limited to authorized vehicles. The vast majority of visitors experience the park via the Transit Bus System or ranger-narrated tour buses. These buses serve two crucial functions: they reduce traffic and pollution, and they enable visitors to travel deep into the wilderness, often stopping for wildlife viewing opportunities as they arise. This restricted-access model ensures that the delicate tundra ecosystem and the wildlife remain protected from the overdevelopment and crowds seen in many other national parks.

The Subarctic Environment and Tundra

The vast majority of Denali’s landscape is characterized by tundra, a subarctic biome defined by permafrost and a short growing season.

The tundra carpet, composed of lichens, mosses, small shrubs, and wildflowers, bursts into color during the short, intense summer, but the underlying permafrost—permanently frozen ground—prevents large trees from taking root and creates the vast, open plains. This environment is extremely fragile; footprints on the tundra can remain visible for decades. Below the tundra lies a band of taiga, or boreal forest, composed of hardy black and white spruce. This harsh climate and terrain demand resilience, both from the wildlife that survive the long winters and the human visitors who venture into this remote corner of North America.