The introduction of Artificial Intelligence into primary and secondary schools is being met with a familiar blend of utopian promise and commercial fervor. Companies and districts alike champion tools that offer automated grading, personalized learning paths, and instant feedback, positioning AI as the ultimate silver bullet for closing achievement gaps and revolutionizing pedagogy. Yet, as the education sector rushes headlong into this new digital frontier, a sobering look at history reveals a pattern of over-hyped technology that failed to live up to its transformative claims. From the era of classroom personal computers to the promise of interactive whiteboards, decades of edtech investment have often resulted in costly, poorly implemented tools that rarely yielded reliable learning gains. The fundamental challenge remains: true pedagogical change requires years of teacher development and cultural adaptation, not just a software update. If we fail to heed the lessons of the past, the current AI boom risks becoming the most expensive, most consequential educational failure yet.

The Historical Failure of Uncritical Adoption

The history of educational technology is a graveyard of brilliant inventions and dashed hopes. In the 1980s, proponents promised that the personal computer would fundamentally reshape learning, but most PCs ended up relegated to specialized labs or used merely for drill-and-practice exercises that digitized existing methods. Similarly, the rapid adoption of interactive whiteboards and large-scale learning management systems often sputtered because the technology was installed without a corresponding, sustained investment in teacher professional development. Educators were simply handed a tool and expected to integrate it flawlessly into complex curricula, resulting in technology being used in shallow, low-impact ways. The core lesson is clear: technology rarely fails on its own; it fails due to a failure of thoughtful implementation and cultural change.

The recurring mistake lies in adopting technology as an additive fix rather than a catalyst for subtractive and transformative redesign. Past edtech was often sold with the seductive pitch of “more,” promising to add convenience without asking teachers to subtract less effective practices or completely rethink their approach. This uncritical adoption leads to what researchers call a “digitization of the status quo,” where technology merely makes inefficient practices marginally faster, rather than enabling entirely new, more effective forms of teaching and learning. True success, as historical analysis shows, requires a long-term horizon, recognizing that it takes several years for new routines, norms, and family support mechanisms to solidify before any novel invention reliably improves student outcomes.

The Paradox of AI and the Teacher’s Labour

The most compelling argument for AI in schools is its alleged power to save teachers’ time, automating everything from lesson planning to personalized feedback. However, new research on generative AI tools in educational settings is revealing a crucial labour paradox. The systems promoted as being effortless often demand a significant, hidden input of human labour to function reliably and ethically. For instance, to ensure an AI tutor or feedback tool is accurate and consistent—to prevent it from “hallucinating” or providing misleading information—an educator must spend considerable time crafting meticulous prompts, curating model answers, and rigorously auditing the AI’s output.

This demand for constant, high-stakes human oversight means that the promise of a time-saving machine often results in a re-allocation of teacher labour rather than a reduction. Instead of grading or preparing materials, teachers are now tasked with becoming AI auditors and prompt engineers, a specialized skill set for which most have received no training. Furthermore, testing of educational chatbots in subjects requiring nuance, such as law, showed high rates of inaccurate or confusing feedback, even when using the latest, most powerful models. The effort required to get the tool to work effectively, consistently, and without introducing errors often outweighs the perceived benefit, leading many time-poor educators to question the tool’s practical value.

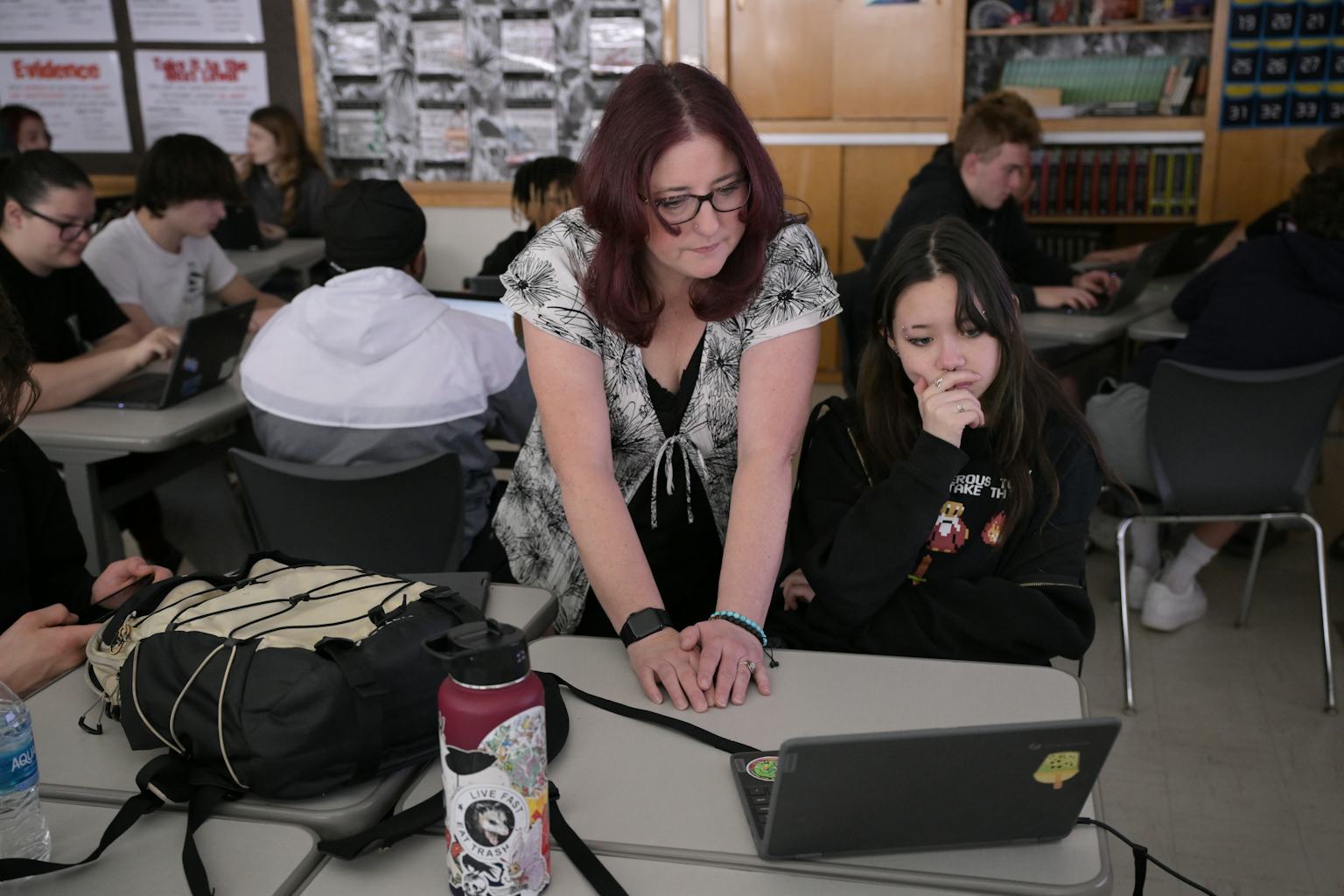

This resistance is compounded by the fact that students still prefer human mentorship. While AI can offer immediate feedback and a conversational tone, making students more comfortable expressing uncertainty, when given a choice between instant AI feedback and delayed human feedback, the vast majority of students opt for the human response. This preference underscores that education is fundamentally a relational activity. The value of feedback is not just in the content, but in the trust and personal investment conveyed by the human educator, a quality that no algorithm can replicate.

The Erosion of Skills and the Digital Divide

A second, more subtle danger of the AI rush is the potential for skill atrophy among students and educators alike. When a student relies on an AI writing tool to bypass the difficult cognitive work of brainstorming, structuring, and drafting an essay, they forfeit the deep learning and critical thinking required to build those skills independently. Educational achievement is not measured by the final product alone, but by the cognitive labour invested in its creation. Offloading this labour to a machine risks creating a generation of students who possess an illusion of competence, able to generate complex-sounding answers but lacking the foundational mental models to scrutinize or defend them.

This challenge is inextricably linked to the issue of equity and access. The history of edtech shows that technological innovation often exacerbates the digital divide, rather than closing it. When budgets tighten, it is typically lower-income and rural districts that suffer first from cuts to maintenance, device renewal, and essential technical support. Furthermore, while affluent schools may have the resources to invest in continuous professional learning—teaching teachers how to use AI for high-impact, transformative tasks—under-resourced schools may be left to use AI for shallow automation, reducing the quality of their educational experience. Without sustainable funding and dedicated support for every educator, AI will become yet another tool that widens the opportunity gap under the guise of progress.

A Blueprint for Human-Centered Integration

To avoid repeating past failures, the integration of AI must follow a human-centered blueprint that prioritizes pedagogical values over commercial hype. This strategy begins with a commitment to rigorous, long-term evaluation before wide-scale deployment. Instead of simply adopting the newest vendor tool, schools must treat AI as an experimental educational aid, testing its reliability, consistency, and true impact on student learning over multiple years. This requires shifting the goal from achieving “AI integration” to achieving “reliable learning improvement,” a benchmark that necessitates evidence-based scrutiny rather than hopeful assumption.

The most vital component of this blueprint is the empowerment of the human teacher. Continuous, high-quality professional learning must be prioritized and sustained, treating teachers not as passive users of a tool, but as co-designers and critical consumers of AI. Teachers need dedicated time and resources to develop new pedagogical norms that effectively integrate AI—for instance, designing assignments that use generative AI to produce a draft, followed by a critical human analysis of the AI’s biases and assumptions. This approach re-frames the student’s task from creation to curation and critique, leveraging the speed of the machine while preserving and elevating the high-value human skills.

Ultimately, the future of AI in schools should be guided by the principle that technology must support human relationships, not replace them. The most successful past uses of technology were those that strengthened the bond between teacher and student, offering new avenues for collaboration, communication, and personalized human mentorship. By focusing on using AI to offload administrative burdens and provide quick, low-stakes feedback, while freeing up teacher time for high-value activities like mentorship, ethical instruction, and deep critical discussion, schools can use this powerful tool responsibly. The lesson from history is not to fear the machine, but to fear the unexamined rush, ensuring that this technology remains a servant to our educational mission, not its accidental master.