Architectural photographer Marc Goodwin has continued his global documentary project, this time turning his lens to the diverse world of Belgian architecture studios. The collection features the workspaces of fourteen different firms across the country, including Antwerp-based Studio Okami and Ghent-based Oyo, offering a rare glimpse into the environments that shape Belgian design. According to Goodwin, who is the founder of photography studio Archmospheres, the series revealed a striking difference in atmosphere and “vibe” between studios located in the capital, Brussels, and those elsewhere in Belgium. Furthermore, the survey highlighted a powerful, encouraging trend shared by Belgian studios and their international peers: a widespread embrace of adaptive reuse and transformation in their own office spaces.

The Brussels-Rest of Belgium Divide

One of the most immediate and insightful observations made by Marc Goodwin during his documentation was the palpable difference in atmosphere between architecture studios situated in Brussels and those located in other Belgian cities. Goodwin noted that the contrast was “sharp,” affecting both the general environment and the creative “vibes” within the workspaces. This distinction suggests that the political and cultural gravity of the capital may influence the character and operation of its design firms in ways that differ from those operating in other major Belgian hubs like Antwerp and Ghent.

While the article does not explicitly detail the nature of this atmospheric difference, the featured studios themselves offer a spectrum of scales and settings. For instance, Brussels-based Brut Architecture and Urban Design occupies a 320-square-meter former office and residential space, while firms outside the capital often inhabit larger, historically industrial or commercial buildings, pointing toward a variance in access to building types and local regulatory environments that may shape the workspace culture.

Adaptive Reuse: A Global and Local Trend

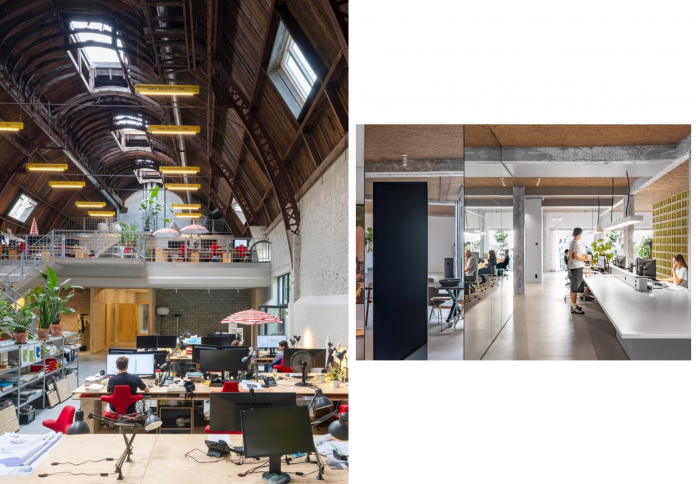

A more encouraging and globally relevant finding from Goodwin’s Belgian series is the pronounced trend of adaptive reuse. The photographer, who has previously documented architecture studios in places like Portugal and Taiwan, noted that the Belgian firms are part of a discernible “global shift” towards transforming and repurposing existing structures. This approach—where old buildings are given new life rather than demolished—is being embraced widely across the international architecture community.

The history of the buildings occupied by the featured studios strongly illustrates this trend. Many of the workspaces are set within formerly industrial or storage facilities, demonstrating the architects’ commitment to the principles of reuse in their own professional environments. B-Architecten, for example, is situated in a massive 1,200-square-meter former factory space, while Robbrecht en Daem Architecten occupies a 1,320-square-meter storage facility. This pattern confirms that the philosophy of adaptive reuse is not merely a theoretical design principle in Belgium but a practical, daily reality woven into the fabric of the studios themselves.

A Spectrum of Size and Scale

The featured collection of fourteen studios provides a comprehensive look at the diverse organizational scales and spatial needs of Belgian architecture practices. The firms documented range from smaller, more intimate operations to large, well-established practices, each occupying a workspace reflective of their team size and operational scope.

At the more compact end of the spectrum is Studio Okami, an Antwerp-based firm with only two staff members working in a 150-square-meter residential building, and I.s.m.architecten, with seven staff in a 100-square-meter former factory. In contrast, larger organizations like B-Architecten and Polo Platform (Antwerp) are substantial operations, with 60 and 63 staff members, respectively, housed in significantly larger spaces—1,200 and 1,230 square meters. This breadth of size highlights the varied structure of the Belgian architecture profession, encompassing boutique design firms and major corporate players, all navigating the country’s unique architectural landscape.

The Workspace as an Architectural Statement

Goodwin’s project underscores the idea that an architecture studio’s workspace is often its most telling architectural statement. By choosing to locate their offices in buildings with rich industrial or commercial histories, the Belgian architects implicitly advocate for the value of transformation and longevity over new construction. The history of the buildings is varied, including a horticulture facility for Stand Van Zaken, a commercial space for Bruno Spaas Architectuur, and an office and storage facility for Polo Platform (Brussels).

The sheer variety of these repurposed spaces—from factories and storage facilities to commercial and residential structures—suggests a highly practical and resourceful design culture in Belgium. This internal commitment to transformation is deemed by Goodwin to be “one of the most inspiring and encouraging things to witness,” linking the domestic Belgian architecture scene to a vital, eco-conscious movement taking place on a global scale.