The historic Delaware Power Station in Philadelphia, a hulking monument of early 1900s industry that lay dormant after 2005, has been dramatically transformed from an engine of energy production into a dynamic engine of fitness and community. Local firms Good City Studio and Hexagon Studio Architects took on the cavernous main turbine hall to create Ballers, a sprawling sports club housing courts for pickleball, soccer, and squash. The design is a bold exercise in adaptive reuse, consciously retaining the site’s rugged, industrial character while injecting it with a vibrant, athletic energy. Rather than concealing the building’s decay, the project leaned into the aesthetic of its abandoned state—including the raw concrete and even the graffiti left by vandals—to inform a minimal, high-impact aesthetic. This conversion is a masterful act of architectural resurrection, celebrating the past while providing a monumental stage for Philadelphia’s new generation of urban recreation.

The Grandeur of the Industrial Shell

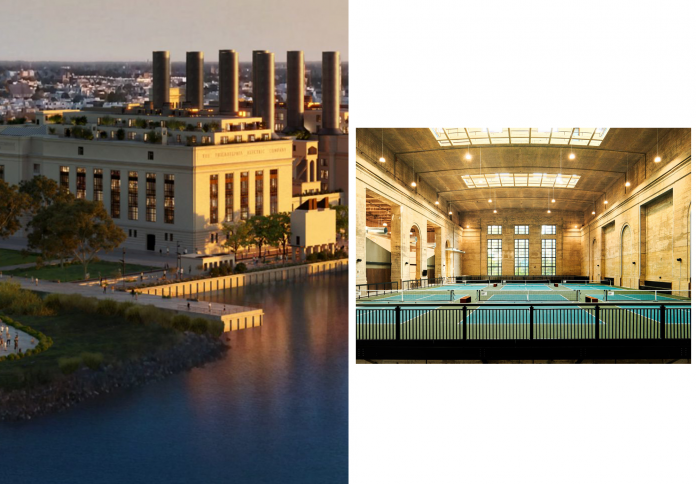

The vast scale of the original industrial architecture was the primary catalyst for the project’s success, offering a unique, column-free canvas that modern construction rarely affords. Ballers occupies the former turbine hall of the Delaware Power Station, a structure built in the early 1900s in Philadelphia’s Fishtown neighborhood and now part of a larger mixed-use complex known as The Battery. This historic space stretches in a dramatic horizontal volume, connecting the original entrance to the waterfront side of the complex, which now features residential units and a rooftop pool positioned strikingly between the site’s defunct smokestacks.

Good City Studio founder and Ballers chief creative officer Amanda Potter noted that the sheer dimensions of the space—a sky-lit hall soaring 75-feet (23 metres) tall with immense stretches of column-free area—were inherently suited for court sports. The turbine hall’s grand ceiling not only created an incredible sense of drama and volume but also provided the necessary vertical clearance required for sports like pickleball and soccer. The immense scale meant the new sports program did not have to fight the existing architecture; rather, the program was able to organically “place itself” within the given structure, respecting the original footprint and celebrating the colossal dimensions of the industrial age.

A Multi-Layered Functional Landscape

The design strategy focused on intelligently inserting a complex sports program across multiple levels without partitioning the monumental space. The facility features a hybrid layout, with sports courts spread intermittently across the ground level and a newly introduced mezzanine level. The sheer height allowed for the strategic layering of function, optimizing every square foot of the vast hall. This resulted in a dynamic interior where the energetic activity on the ground floor is overlooked and complemented by more specialized, elevated spaces.

Specific sports found their perfect fit within the existing structural conditions. The larger, open floor of the turbine hall accommodates the full courts for pickleball and indoor soccer. Meanwhile, more focused activities, such as golf simulators and squash courts, were precisely slotted into a more narrow loggia space on the second floor. Potter described how these courts fit “to the inch” within the existing architectural recesses. At the geometric and social center of the floor plan, a partially enclosed concrete volume was built to house the restaurant and bar, creating a defined gathering spot that contrasts with the open fields of play while still sitting physically beneath the high ceiling of the original hall. This strategic placement ensures that food, drink, and socializing are central to the club experience, serving as a hub connecting all the disparate activities.

Honoring the Aesthetic of Decay

One of the most compelling aspects of the Ballers project is its embrace of the building’s post-industrial history, specifically its period of abandonment. Rather than pursuing a glossy, pristine new build, the designers chose an aesthetic that was directly informed by the power plant’s derelict state, where it had been “overtaken by weather, vandals, and some rather talented graffiti artists.” This decision to celebrate the grit and patina of the ruin is a key tenet of the adaptive reuse approach, providing an authentic layer of history that new materials cannot replicate.

The project minimized new cladding and interior finishes, preserving the raw concrete and exposed materials of the original industrial shell. To ensure the vibrant aesthetic of the abandoned period was not merely sanitized but intentionally integrated, the design team commissioned local graffiti artists, including Tiff Urquehart, to formally tag the walls. This act transforms what was once vandalism into a legitimate layer of artistic expression and design, weaving the building’s recent counter-cultural history directly into its new identity. This curated rawness offers a powerful visual tension, where the sleek lines of the new sports courts contrast sharply with the rough, art-covered walls, creating an atmosphere that is intentionally urban, unpolished, and intensely unique to Philadelphia.

High-Design Interventions and Personal Detail

Amidst the raw concrete and intentional graffiti, the design introduces carefully selected elements of high-design and personalized detail that serve to soften the industrial scale and inject character. The central concrete volume, which houses the restaurant and bar and is nestled under the mezzanine level, becomes a moment of focused, human-scale intervention. This area is designed to feel intimate and stylized, contrasting with the epic, functional spaces surrounding it.

Good City Studio founder Amanda Potter incorporated numerous vintage pieces and personal elements into these social spaces, ensuring the club felt less like a utilitarian gym and more like an extension of a designer’s personal vision. The most striking of these personal touches is the bright-yellow, steel cage that stands prominently behind the bar. This piece was explicitly informed by Potter’s teenage love for the iconic 1990s aesthetic of designer Gianni Versace, serving as a playful, nostalgic nod to that era of maximalist design. This use of bold color and unique, repurposed, or custom-designed objects adds a layer of unexpected glamour and personality. By juxtaposing the monumental structural elements of the former power station with such vibrant, tailored design pieces, Ballers achieves a powerful synthesis: a historic building that feels contemporary, raw yet polished, and universally athletic yet deeply personal.